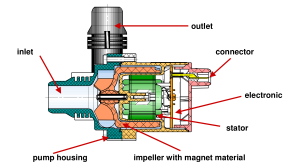

Here’s another Diesel-fired heater related project – these Webasto heaters are fitted to Jaguar S-Type cars as auxiliary heaters, since (according to the Jag manual), the modern fuel-efficient diesels produce so little waste heat that extra help is required to run the car’s climate control system. (Although this seems to nullify any fuel efficiency boost, as the fuel saved by not producing so much waste heat in the engine itself is burned in an aux heater to provide heat anyway). The unfortunate part is these units don’t respond to applying +12v to Pin 1 of the ECU to get them to start – they are programmed to respond to CAN Bus & K-Line Bus only, so they require a bit more effort to get going. They also don’t have a built-in water circulation pump unlike the Webasto Thermo Top C heaters – they expect the water flow to be taken care of by the engine’s coolant pump.

The water ports are on the side of this heater instead of the end, the heat exhanger is on the left. These hearers are fitted to the car under the left front wing, behind a splash guard. Pretty easy to get to but they get exposed to all the road dirt, water & salt so corrosion is a little problem. The fuel dosing pump is in a much more difficult spot to get at – it’s under the car next to the fuel tank on the right hand side. Access to the underside with stands is required to get at this.

The ECU side has all the other connections – Combustion air, exhaust, fuel, power & control.

Only two of the external connectors are used on these heaters, the large two pin one is for main power – heavy cable required here as the current draw can climb to ~30A on startup while the glow plug fires. The 8-pin connector on the left is the control connector, where the CAN / K-Line / W-Bus buses live. The fuel dosing pump is also supplied from a pin on this connector. The small 3-pin under that is a blank for a circulation pump where fitted. Pinouts are here:

| Pin | Signal |

|---|---|

| 1 | Battery Positive |

| 2 | Battery Negative |

| Pin Number | Signal | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Telestart / Heater Enable | Would usually start the heater with a simple +12v ON signal, but is disabled in these heaters. |

| 2 | W-Bus / K-Line | Diagnostic Serial Bus Or Webasto Type 1533 Programmer / Clock |

| 3 | External Temp Sensor | |

| 4 | CAN- | CAN Bus Low |

| 5 | Fuel Dosing Pump | Fuel Pump output. Connect pump to this pin & ground. Polarity unimportant. |

| 6 | Solenoid Valve | Fuel cutoff solenoid optionally fitted here. |

| 7 | CAN+ | CAN Bus High |

| 8 | Cabin Heater Fan Control | This output switches on when heater reaches +50°C to control car heater blower |

| Pin | Signal | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ? | ? |

| 2 | Circulation Pump + | |

| 3 | Circulation Pump - |

Removing the clipped-on plastic cover reveals the other ECU connectors. The large white one feeds the glow plug, & the large multi-pin below brings in the temp & overheat sensor signals.

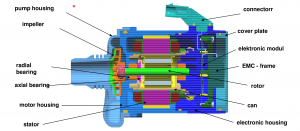

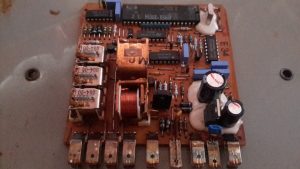

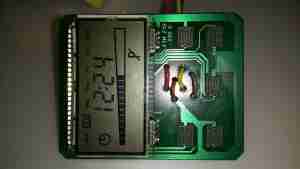

The heart of the ECU is a massive microcontroller, a Freescale MC9S12DT128B, attached to a daughterboard hooked into the ECU power board.

The high power section is on the board just under the connectors, here all the large semiconductors live for switching the fan motor, glow plug, external loads, etc.

The bus transceivers are separate ICs on the control board, a TJA1041 takes care of the CAN bus. There’s also a TJA1020 LIN bus transceiver here, which is confusing since none of the Webasto documentation mentions LIN bus control.

The combustion fan motor is in the ECU compartment, nicely sealed away from the elements. There is no speed sensor on these blowers, unlike the Eberspacher ones.

The motor is a Buhler, rated at 10.5v.

Unclipping the cover from the other end reveals the combustion fan, it’s under the black cover. (These are side-channel blowers, to provide the relatively high static pressure required to run the burner).

The overheat & temperature sensors are on the end of the heat exchanger, retained by a stainless clip.

With the clip removed, the sensors can be seen better. There’s some pretty bad corrosion of the aluminium alloy on the end sensor, it’s seized in place.

The heater splits in half to reveal the evaporative burner itself. I’ve already cleaned the black crud off with a wire brush here, doesn’t look like this heater has seen much use as it’s pretty clean inside.

Inside the burner the fuel evaporates & is ignited. There is a brass mesh behind the backplate of the burner to assist with vaporisation.

The glow plug is fitted into the side of the burner ceramic here. This is probably a Silicon Carbide device. It also acts as a flame sensor when the heater has fired up. The fuel inlet line is to the left under the clamp.

The hot gases from the burner flow into the heat exchanger here, with many fins to increase the surface area. There’s only a couple of mm coating of carbon here, after 10 years on the car I would have expected it to be much more clogged.

I’m currently waiting on some components to build an interface so I can get the Webasto Thermo Test software to talk to the heater. Once this is done I can see if there are any faults logged that need sorting before I can get this heater running, but from the current state it seems to be pretty good visually. More to come once parts arrive!

The full service manual for these heaters can be grabbed from here, along with the wiring details for the Jaguar implementation & the Thermo Test software for talking to them:

[download id=”5618″]

[download id=”5620″]

[download id=”5622″]