As with *any* laser, proper precautions must be taken to avoid any possibility of damage to vision. The types of He-Ne lasers mostly dealt with in this document are rated Class II, IIIa, or the low end of IIIb (see the section: Laser Safety Classifications. For most of these, common sense (don’t stare into the beam) and fairly basic precautions suffice since the reflected or scattered light will not cause instantaneous injury and is not a fire hazard.

However, unlike those for laser diodes, He-Ne power supplies utilize high voltage (several kV) and some designs may be potentially lethal. This is particularly true of AC line powered units since the power transformer may be capable of much more current than is actually required by the He-Ne laser tube – especially if it is home built using the transformer from some other piece of equipment (like an old tube type console TV or that utility pole transformer you found along the curb) which may have a much higher current rating.

The high quality capacitors in a typical power supply will hold enough charge to wake you up – for quite a while even after the supply has been switched off and unplugged. Depending on design, there may be up to 10 to 15 kV or more (but on very small capacitors) if the power supply was operated without a He-Ne tube attached or it did not start for some reason. There will likely be a lower voltage – perhaps 1 to 3 kV – on somewhat larger capacitors. Unless significantly oversized, the amount of stored energy isn’t likely to be enough to be lethal but it can still be quite a jolt. The He-Ne tube itself also acts as a small HV capacitor so even touching it should it become disconnected from the power supply may give you a tingle. This probably won’t really hurt you physically but your ego may be bruised if you then drop the tube and it then shatters on the floor!

However, should you be dealing with a much larger He-Ne laser, its power supply is going to be correspondingly more dangerous as well. For example, a 35 mW He-Ne tube typically requires about 8 mA at 5 to 6 kV. That current may not sound like much but the power supply is likely capable of providing much more if you are the destination instead of the laser head (especially if it is a home-made unit using grossly oversized parts)! It doesn’t take much more under the wrong conditions to kill.

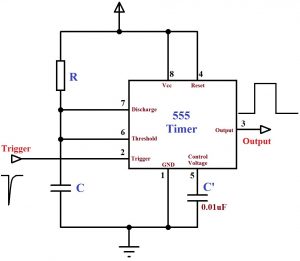

After powering off, use a well insulated 1M resistor made from a string of ten 100K, 2 W metal film resistors in a glass or plastic tube to drain the charge – and confirm with a voltmeter before touching anything. (Don’t use carbon resistors as I have seen them behave funny around high voltages. And, don’t use the old screwdriver trick – shorting the output of the power supply directly to ground – as this may damage it internally.)

And only change electrical connections or plug/unplug connectors with power OFF, being aware of the potential for stored charge. In particular, the aluminium cylinder of some HeNe laser heads is the negative return for the tube current via a spring contact inside the rear end-cap. So, pulling off the rear end-cap while the laser is powered will likely make YOU the negative return instead! You will probably then bounce off the ceiling while the laser bounces off the floor, which can easily ruin your entire day in more ways than one. 🙁 🙂 This connection scheme is known to be true for most JDS Uniphase and many Melles Griot laser heads, but may apply to others as well.

Now, for some first-hand experience:

(From: Doug (dulmage@skypoint.com).)

Well, here’s where I embarrass myself, but hopefully save a life…

I’ve worked on medium and large frame lasers since about 1980 (Spectra-Physics 168’s, 171’s, Innova 90’s, 100’s and 200’s – high voltage, high current, no line isolation, multi-kV igniters, etc.). Never in all that time did I ever get hurt other than getting a few retinal burns (that’s bad enough, but at least I never fell across a tube or igniter at startup). Anyway, the one laser that almost did kill me was also the smallest that I ever worked on.

I was doing some testing of AO devices along with some small cylindrical HeNe tubes from Siemens. These little coax tubes had clips for attaching the anode and cathode connections. Well, I was going through a few boxes of these things a day doing various tests. Just slap them on the bench, fire them up, discharge the supplies and then disconnect and try another one. They ran off a 9 VDC power supply.

At the end of one long day, I called it quits early and just shut the laser supply off and left the tube in place as I was just going to put on a new tube in the morning. That next morning, I came and incorrectly assumed that the power supply would have discharged on it own overnight. So, with each hand I stupidly grab one clip each on the laser to disconnect it. YeeHaaaaaaaaa!!!!. I felt like I had been hid across my temples with a two by four. It felt like I swallowed my tongue and then I kind of blacked out. One of the guys came and helped me up, but I was weak in the knees, and very disoriented.

I stumbled around for about 15 minutes and then out of nowhere it was just like I got another shock! This cycle of stuff went on for about 3 hours, then stopped once I got to the hospital. I can’t even remember what they did to me there. Anyway, how embarrassing to almost get killed by a HeNe laser after all that other high power stuff that I did. I think that’s called ‘irony’.

Comments on HeNe Laser Safety Issues

(Portions from: Robert Savas (jondrew@mail.ao.net).)

A 10 mw HeNe laser certainly presents an eye hazard.

According to American National Standard, ANSI Z136.1-1993, table 4 Simplified Method for Selecting Laser Eye Protection for Intrabeam Viewing, protective eyewear with an attenuation factor of 10 (Optical Density 1) is required for a HeNe with a 10 milliwatt output. This assumes an exposure duration of 0.25 to 10 seconds, the time in which they eye would blink or change viewing direction due the uncomfortable illumination level of the laser. Eyeware with an attenuation factor of 10 is roughly comparable to a good pair of sunglasses (this is NOT intended as a rigorous safety analysis, and I take no responsibility for anyone foolish enough to stare at a laser beam under any circumstances). This calculation also assumes the entire 10 milliwatts are contained in a beam small enough to enter a 7 millimeter aperture (the pupil of the eye). Beyond a few meters the beam has spread out enough so that only a small fraction of the total optical power could possible enter the eye.